Motherland reality: As simple as drawing lines on a map

By Jehron Muhammad | Last updated: Nov 21, 2013 – 11:33:56 AM

http://www.finalcall.com/artman/publish/World_News_3/article_100986.shtml

|

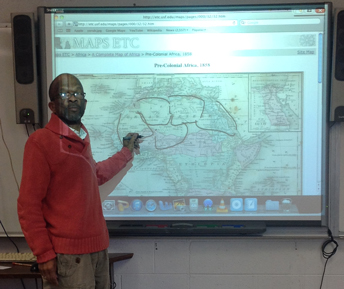

(FinalCall.com) – To show students how Africa was divvied up in 1885 by Europeans, I stood in front of my son Equiano’s sixth grade class at Germantown Friends School in Philadelphia and armed only with a magic marker, he drew “artificial borders” on a map of Africa, devoid of its current nation states, that was projected from the Internet onto an erasable board.

According to the documentary “Scramble for Africa,” the 1885 Act of Berlin did the same thing—carve up Africa by simply drawing lines on a map. “Places where they had not even been yet. Between 6,000 and 10,000 political units were carved up.

“People … were just cut off from (water sources) … it was complete geographical madness,” recounted the documentary.

Acquainting 11- and 12-year-olds with a system of exploitation that has spanned the globe was truly a daunting task. But teaching the history of European land acquisition by the might of arms as the invaders’ method of “development” is the principal missing ingredient in Western education and deserves much discussion, research and reflection.

During the class we read from Sol T. Plaatje’s 1916 book, “Native Life In South Africa.” The author chronicles events after implementation of the 1913 Native Land Act.

Projecting a map of Africa onto an erasable board, Mr. Muhammad draws lines on a map of the continent similar to how Africa was carved up by European powers in 1885.

|

The Act institutionalized exploitation of South Africa’s native population similar to the American system of exploitation called sharecropping that grew out of the need for former slave masters to exploit the labor of their recently freed slaves.

“There were two reasons for the introduction of the Natives’ Land Act: black farmers were proving to be too competitively successful as against white farming and there was a demand for a flow of cheap labor to the gold mines.”

After the African slave trade the Industrial Revolution had a need for raw materials and labor to fuel a new economic engine. “The advent of the machine was transforming the (European) continent into the workshop of the world,” according to Scramble For Africa, “a workshop in need of raw material.”

In South Africa not only were Black farmers forced off of the land of their ancestors, if they stayed they were required to labor exclusively for their new masters. Before the new law, Blacks paid 50 percent of their harvest for the right to live on the land. Afterward they could no longer benefit from the cattle they owned since the law said livestock was now under the control of the White land owner.

The natives, write Plaatje, were expected to give Whites free labor but Whites actually wished the natives could in addition “breed slaves for them.”

My son’s class was assigned to read two recent articles about land exploitation in Zimbabwe and South Africa that originally appeared in The Final Call. They also were required to ask questions, which provided stimulus for a lively and informative discussion.

To give insight and to show the widespread reach of this particular form of exploitation, the class was told land expropriation in Zimbabwe and South Africa was similarly experienced in all of Southern Africa including Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland and Zambia.

Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe

|

The class was also made aware that the reason Western powers are so anti-Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe was in fear that his expropriation of land from Whites, who originally took it from native Africans, could represent a catalyst for taking land back in South Africa and the entire region.

According to a “Review of Land Reforms In Southern Africa,” “The countries of southern Africa share similar histories of colonization and dispossession, histories that continue to shape current patterns of land tenure and administration. Most of the countries in the region have been through a phase of liberalization and market reforms, or market-related land redistribution programs, and since the 1990s new land laws have been passed in several countries, which tend to have been relatively weakly implemented and enforced.”

South Africa is a case in point. Coming out of prison, many said Nelson Mandela was a nationalist. But by the time he became president, according to published reports, he insisted that the African National Congress had been “cleansed” of this sort of ideology—an obvious response to being schooled on the reality of the global economy. The ANC’s new market economy commitment even was given the appearance of a payoff: Five months before the ANC came into power it signed a letter “of intent with the IMF (International Monetary Fund) committing itself as the future government to a program of fiscal austerity in return for an $850 million loan.”

Did the ANC capitulate, did it submit to market realities at the expense of the people who fought, died and suffered during the liberation struggle? Or was the ANC faced with a dilemma to either stand up to market forces, try and create a kind of stimulus program for the people, and face the wrath of the Whites who controlled the economy, and who Mandela felt were needed allies?

The ANC Department of Economic Policy received its training at Goldman Sachs in New York and developed a policy relying on the conventional wisdom of the IMF and World Bank “emphasizing”—according to former South African President Thabo Mbeki’s biography “A Legacy of Liberation”—a limited state and the encouragement of private sector growth.

The ANC’s land redistribution program that said 30 percent of agricultural land was to be transferred from White farmers to Blacks within the first five years of South Africa’s new democracy was proposed by the World Bank.

By the end of 1999 barely one percent of the land had been transferred from White to Black hands. Now approaching 2014 with barely seven percent of agricultural land in Black hands, the program has been described as a dismal failure.

And with elections in 2014, the Jacob Zuma administration in South Africa, along with Goldman Sachs, (read the report: South Africa-20 Years of Freedom) is trying to paint an encouraging but flawed picture of 20 years of ANC rule. The trouble is neither President Zuma nor Goldman Sachs have shown a willingness to institute a program to right the wrongs of its poor suffering Black masses.

Great Britain pledged to compensate White farmers in Zimbabwe for expropriated land only to renege. The year 2014 will represent two strikes showing the failure of the South African land reform program. With growing dissatisfaction in South Africa, what will strike three represent?

Jehron Muhammad, who writes for The Final Call from Philadelphia, can be reached at Jehronn@msn.com. Twitter: @JehronMuhammad.